- Home

- Catrina Davies

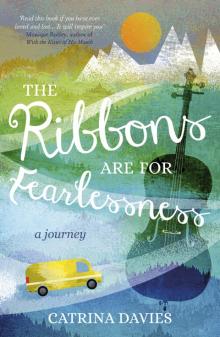

The Ribbons Are for Fearlessness Page 10

The Ribbons Are for Fearlessness Read online

Page 10

Which is pretty much how it was for me, too.

But first I had to get the wetsuit on, which took about half an hour, the wetsuit clearly having been made for a girl about half my size. I couldn’t help wondering who she was. Børge’s girlfriend? Ex-girlfriend? Maybe it brought up bad memories. Maybe that’s why he had stalked off like that.

Once I was finally shrink-wrapped in black neoprene, looking about as attractive as a dog with rigor mortis, I picked up the board and staggered over the rocks with it to the beach. Little pieces of foam floated through the air like snowflakes. I tied the board to my ankle with the leash and waded into the water up to my knees. Johan paddled over.

“Try to get to your feet,” he said, “and watch the rip.”

Which was not very helpful at all.

I could see the rip. It was a current like a small river, where some of the energy from the waves was traveling back out to sea. Johan and Børge used it like a conveyor belt to take them out, behind where the waves were actually breaking. I was determined to stay right where my feet could still touch the bottom. Unfortunately, this was exactly where the waves were breaking. On my head.

“It’s only water,” said Johan, paddling over for a second time. “You look like you’re waiting for a train to hit you.”

“That’s exactly how I bloody feel,” I yelled after him as he paddled back out.

It’s not that I wasn’t used to the sea. I had grown up with the sea. It’s just that I didn’t usually go swimming in a fresh storm with head-high waves, a massive rip, little pieces of foam floating through the air like snowflakes, and gale force winds. Nor would I normally attach myself by the ankle to eight feet of fiberglass. Watching a wall of water hurtling toward you while you are attached by the ankle to eight feet of fiberglass is exactly like waiting for a train to hit you. There is nowhere to go. When I tried to dive under them, like I would have done if I had been swimming, the board dragged me down and tried to drown me. When I tried to jump over them, it did its best to knock me out. And that was just dodging waves. Catching them was laughable. Even when there was a lull long enough for me to manage to get myself on to the board, I’d be knocked straight off again sideways, or headfirst, the board landing on top of me a few moments later.

I dragged myself out and sat on the beach. I hated the fucking sea. I wanted to peel off that disgusting wetsuit and dry myself with a towel and make a cup of tea and sit on a rock and drink it without being bashed around the head. I gazed longingly at the van. Damn that sweet, petite bloody surfer. And Hanna’s bloody ribbons. And Børge, who was just waiting for me to give up. I forced myself back in. I wasn’t going to catch any waves. I was in absolutely no doubt about that. But maybe I could at least learn to lie on the board and paddle.

I was so busy with this that I didn’t notice I had drifted over into the rip until I was quite far out. The waves weren’t breaking on my head anymore. In fact it was oddly calm. I struggled into a sitting position and looked around for Børge and Johan. But for some reason they were paddling away from me as fast as they could, out to sea. Then I understood why. It all happened so fast. The horizon went black and there was this eerie silence. Then the most enormous wave I had ever seen in my life thundered toward me. Børge and Johan just made it over before it broke. I didn’t. It picked me up like a piece of driftwood and threw me headfirst over my board. My leash snapped. The wave played with me like a cat plays with a mouse it’s about to eat. It tossed me this way and that, pulling my body in every direction at once, holding me under until I had no idea which way was up. I was panicking, gasping for breath, gagging on salty water and seaweed. Something grabbed my arm.

“What the hell are you doing?”

A pair of slate-blue eyes was glaring into mine. I spat water out of my mouth. I couldn’t speak.

“Hold on to my ankles,” said Børge.

I spent the rest of the day sitting on the floor of the van, trying to read Hanna’s book, staring out to sea. My body felt stretched and shaken out. It wasn’t a bad feeling, to tell you the truth, although I couldn’t imagine I’d ever try surfing again. When evening came, Johan made a fire on the beach. I watched him from the van as he collected wood from the forest, brought it back, and stacked it in the middle of a circle of rocks. I watched him light the fire and then, when it was going, walk up the beach toward me.

“What are you doing?”

“Hiding.”

“Why?”

“Didn’t you hear? I nearly drowned. Børge had to rescue me.”

“He said you handled it pretty well.”

“What?”

“It’s my fault. I should have told you not to go in today. Even I was shitting it when that set hit. Swell’s dropping. Tomorrow’ll be a different story.”

I shook my head.

“I don’t think I’m cut out for surfing.”

It had been worse than Oslo. Worse even than getting stuck halfway up that cliff with Jack.

“I reckon you are. You’re still alive, aren’t you? Most people have to wait years for that kind of experience. You’re lucky. You got it out of the way right off. Normal waves won’t rattle you now. You’ll get back in. Just don’t listen to idiots like me.”

“I’m not listening,” I said.

But I was.

We walked together to the beach. I sat down on a boulder. Johan handed me a beer. Børge was standing with his back to us, his big frame silhouetted against the darkening sky. The air smelled of salt and there was a thin slice of moon overhead, although it was still light.

“That’s the first moon I’ve seen for six weeks.”

“How long have you been in Norway?”

“Since June.”

“Why Norway?”

“Running away, I suppose.”

“Didn’t work for me,” said Børge, bending down to split a big piece of wood.

Johan had to work hard to get me back in the sea, but he managed it. Mainly because the waves were a lot smaller the next day and the wind had dropped and the whole thing seemed a lot less terrifying. I think Johan felt responsible for my near-death experience, because he stayed in the shore break with me for ages, pushing me onto waves and showing me what I was supposed to do. I still couldn’t do it. I didn’t even come close. In fact, the more I tried, the more I realized that surfing was an utterly ridiculous activity. Like attempting to balance on a tin tray going over a waterfall. But the sun was out and when Johan finally paddled off to join Børge, I stayed in the shore break on my own, trying to stand up again and again until my body had that stretched, salty, wrung-out feeling that made me forget everything, even Jack, even the sweet, petite surfer. Or, if I didn’t exactly forget, I was too tired and salty to care.

I quickly became an addict. As the week progressed it was as if all the salt water I swallowed every day was slowly washing the inside of my mind. The sea was like an anaesthetic. At night I fell easily into a deep, dreamless sleep. In the mornings I could hardly drink my coffee fast enough before I was squeezing myself back into the wetsuit for another fix. I stopped thinking about Jack. I stopped feeling sad about Andrew. I stopped thinking about anything at all, in fact, except my new and utterly engrossing relationship with waves and trying to ride them. I was hooked, in other words. Like a junkie.

The only thorn was Børge. He didn’t get any easier. In the sea I sometimes caught him staring at me, and I imagined he was shaking his head in disgust. Presumably because I was part of the “curse” of everyone wanting to be a surfer. It’s a measure of how addicted I was that I didn’t let his attitude put me off. Johan made up for Børge’s brooding silence in the evenings by the fire by talking at least twice as much as a normal person.

When I was neither in the sea or by the fire I tucked myself in amongst the rocks in front of the van and read Hanna’s book. Even though it was easily the strangest book I had ever come across, far stranger than Jack’s book of Japanese death poems, it was oddly comforting. I read it as sl

owly as possible. I didn’t want to finish it.

Once Børge came and squatted next to me.

“I was just going to make tea,” I said, nervously.

He nodded. I went to the van and boiled the kettle. I could see Børge outside on the rocks. He was flicking through the book, stopping every now and then to stare intently at it. His hair was like mine, frizzy and half dreadlocked from the sea. If he ever smiled he’d probably be quite good-looking. His body was okay anyway. Wide shoulders and long legs, like Jack, only taller. I set the red tin teapot and two mugs down on a rock.

Børge closed the book. “Where did you get this?”

“The same girl who told me about Unstad.”

There was an awkward silence.

“What’s Svolvær like?” I said at last.

“It’s just a town. Nothing special.”

“Is there a shopping center?”

“You want to go to a shopping center?”

“I need to get some money.”

“There’s a post office in Eggum,” said Børge.

Eggum was the next village.

“I need to go busking,” I said at last. “So I can buy diesel.”

“Busking?”

“Playing music on the street.”

“I know what it frigging is. What do you play?”

“Cello.”

“You’ve got a cello in your van?”

It was true that I hadn’t taken it out all week. I hadn’t even thought about it all week. I remembered that I had wanted to learn “Bruca Maniguá.” I poured out two cups of tea and handed one to Børge.

“That’s a pretty cool way to fund a surf trip.”

“Strictly speaking it’s not a surf trip,” I said. “Since I can’t actually surf.”

“Who cares,” said Børge. “You can play the frigging cello.”

I left Unstad and spent one night in Svolvær; a tiny, scrubbed-looking town hemmed in by the open sea to the south, fjords to the east and west, and mountains to the north. In the end I taught myself “Bruca Maniguá” right there on the street, remembering as much as I could and making the rest up as I went along. I couldn’t get enough of it. Pieces of music are a bit like people. Sometimes you just fall in love with them for no particular reason. And I couldn’t help noticing that the pieces of music I had fallen in love with were the ones that I ended up making the most money out of. “Vocalise” in Tromsø and now “Bruca Maniguá” in Svolvær. In two days I made over a hundred pounds, a thousand kroner, mainly from Spanish and Portuguese tourists who had come to see the place where baccalao is made. I couldn’t wait to get back to Unstad and tell Børge. I spent half the money on a fresh tank of diesel, put some aside for a ferry, and blew the rest on cheese and wine and smoked salmon. Because right then it didn’t seem to matter if it took me ten years to get back to Bergen. And because the smoked salmon was ridiculously cheap. The first thing I’d found that was cheaper in Norway than it was in England.

On the long drive back to Unstad I noticed once again how white the sand was on the beaches that ringed the mysterious-looking fjords and inlets, making them look almost tropical. And how fast people drove compared with the mainland, overtaking in a lawless fashion on blind corners. And how many bridges there were. Long, spindly bridges and short, fat bridges and elegant, white bridges like spiderwebs. And how away from the coast there was nothing but dense, rocky mountains, as if I was driving along the bottom of some giant, rugged boulder.

Navigating the endless twisting lane was like going home. When I popped out of the final tunnel I saw that Johan had already lit the fire. He was walking across the beach with a pack of beers. Børge was snapping wood against a rock. I put the van back exactly where it had been, opened the back doors, and watched the sea for a while. It was calm that night, calm and still. I could have stayed there forever. But storms were forecast, and Børge said that when they hit it would rain every day until Christmas.

I didn’t believe him.

I should have.

21

The storms held off long enough for me to stand up and ride a wave all the way to the beach. A proper green wave, too, not just white water. I got to my knees first, and lumbered to a standing position about as ungracefully as possible, and once standing I wobbled a great deal, but I didn’t fall off. Or at least, not until the wave had broken and I was on the beach in six inches of water. Johan whooped. The swell had dwindled to nothing. It was too small for him and Børge to bother getting in.

They held off long enough for me to read the final sentence in Hanna’s book, which was about perseverance. And they held off long enough for us to climb the flat-topped mountain-like headland, south of the beach. They called it the Hammer. It was the biggest of all the mountains that circled the bay, with crumbling sides and a sheer cliff at the front that plunged straight down on to the boulders that stuck out of the sea below. I didn’t want to climb it. I couldn’t think of anything I’d rather do less.

“I hate climbing,” I said.

“It’s not climbing!” Johan hooted with laughter. “You could drive a car up there.”

You couldn’t.

“I’m going to stay and surf.”

“There are no waves.”

He was right. That day it really was flat. Like a millpond. Too flat even for me.

“The calm before the storm,” said Børge, pointing to the thick black clouds that were stacking up on the horizon.

“Come on!” said Johan, jumping on my back and nearly pushing me over. “It’s easy.”

I glanced at Børge. His face was totally impassive, as usual.

“Fuck. Okay.”

Johan was right. It was easy. Much easier than it looked. Not only that but all the way up we picked wild blueberries, stuffing handfuls of them into our mouths like starving children. At least Johan and I did. Børge didn’t seem to like blueberries. When I got to the top he was sitting on a flat piece of rock, staring out to sea. Johan was nowhere to be seen. I sat on the flat piece of rock a few feet away from Børge. The view was outrageous. You could see for miles along the empty coastline in both directions and to the empty horizon, where the clouds were gathering.

“I don’t want to ever leave.”

“You will when it starts raining.”

Since the day I arrived, when white flakes of foam floated through the air like a blizzard and I nearly drowned, the sun had shone pretty much constantly, even if it hadn’t always been that warm.

“Unstad must like you,” Johan had said. “It wants you to come back.”

“Where will you go?” said Børge.

“Back to Bergen, I suppose.” My mouth dried up. “Get a ferry to England.” I felt sick.

“Why England?”

“I’ve been on the road for three months.”

A cloud passed over the sun.

“So?”

“Can’t bum around forever.”

“Why not?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know.”

“If I were you, and I didn’t have to go back to work, I’d bum around for long enough to spend the winter someplace warm that gets good waves, like Morocco or Portugal.”

“What’s your work?”

“I’m a mountain guide. In the French Alps.”

“Is that where you live?”

“I guess.”

It sounded like Børge felt sick at the thought of going home, too. Maybe his ex, the one whose surfboard I had, hated him and made his life a misery. Maybe she’d left him for a sophisticated and charming man, who liked blueberries and wore technical trousers. I wanted to ask him. I wanted to tell him that I knew exactly how he felt. Instead I said, “What happens to Unstad?”

Børge yawned.

“Fishermen come from Sweden, towing wooden huts, which they park on the frozen lake. Johan goes snowboarding in the morning and surfing in the afternoon. The tourists stay in Svolvær.”

The sun was still shining when we got back to the beach, bu

t the horizon had disappeared. Børge didn’t like the look of it. Johan drove to Eggum and called his Polish housemates. One of them worked for the tourist office. She said she could wangle me a free passage on the ferry to Bodø the following morning. Børge and Johan would go back to Moskenes.

We were all silent that night. The fire was smaller than usual because we’d used nearly all the wood and Johan couldn’t be bothered to go and get any more, now that we were leaving. I leaned back against a rock and listened to the sea. I felt sad.

Sometime later Børge went to the bus and came back with something in a plastic bag. He chucked it at me. I took it out of the bag. It was a Patagonia duck down coat. Just like Jack’s, only small and red and tailored for a woman. I held it up against myself.

“Try it on,” said Børge.

It fit me perfectly. Whereas Jack’s was huge and square, the sleeves hanging half a foot off the ends of my arms, this one could have been made for me. Børge’s expression, as usual, was impossible to read.

“Are you giving this away?” I said, at last.

“No frigging way.”

“Then what are you doing?”

I took it off. I wanted to ball it up and throw it at him.

“Patagonia send me clothes every year. I’m supposed to get photos of people in them for the catalogue. I thought it would look good on you. Especially if you were playing your cello.”

“What do you do with the clothes when you’ve got the photos?”

Maybe he would sell it to me cheap.

“If the photo goes in the catalogue and I get paid I let the model keep it.”

I put the coat on again. It was like arms, holding me close. I wanted it so much, I’d even play my cello in front of him. I stood up.

“I’ll go and get it.”

Børge shook his head.

“Can’t do it here. It’s a winter coat. We need snow. Maybe if you came to the Alps.”

“The Alps are fucking miles away.”

“So is Nordkapp.”

“I haven’t got a heater.”

The Ribbons Are for Fearlessness

The Ribbons Are for Fearlessness