- Home

- Catrina Davies

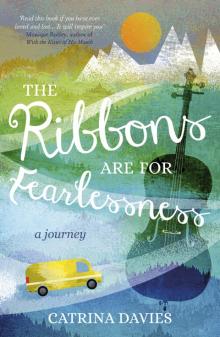

The Ribbons Are for Fearlessness Page 6

The Ribbons Are for Fearlessness Read online

Page 6

I practically lived in those rivers. I washed in them. I washed my clothes in them. I washed my hair in them. I did my washing up in them. I drank them. When they were vigorous I showered under powerful waterfalls. When they were lazy I lay naked in them as if they were a tepid bath. I listened to them as if they were music. I had no buzzing fridge, no fizzing lightbulbs, no gurgling pipes. There was no distant hum of traffic. There were no voices in the street. There were no streets. There was nothing, apart from the crackling of a candle flame and the voices in my head, the memories that wouldn’t leave me alone, that pestered me like the whining of mosquitos.

Dead.

I wish I could feel you naked beside me.

Dead.

Nothing.

We could be troubadours.

I would have run from them, distracted myself in some way, called someone, drunk something, watched something on television, but all I could do was wait and hope they would fade. I sat on the back step of my old, rusting van and stared out at the mountains or the river or whatever that night’s backdrop was, and gradually they did fade. The memories and the past they belonged to were swallowed up by the silence, like everything else. If I had known how lonely and remote those park-ups were going to be, I would have been gripped with terror at the thought of it, but it never got dark, and gradually I realized that I was not afraid.

Aside from the time I spent at Jan Erik’s, I had survived for a month on milky coffee, porridge, pasta, rollmops, and grated carrots. I saved all the bigger coins for diesel, which meant that visiting supermarkets was a fraught experience involving fistfuls of coppers, which I would painstakingly count at the checkout while people piled up behind me. I didn’t have much choice. I couldn’t exactly go to a bank. I never knew quite how much I had, either, although I grew more and more skilled at guessing from the weight of the coins in my hands. When I was short by a few kroner the lady at the checkout would usually let me off, because she couldn’t face the thought of counting all those coins again.

I reached Mo i Rana on 14 July. It’s an old industrial town from which all the industry has long since departed. These days the streets are lined with benches, on which elderly ladies and gentlemen gathered to listen to me play my cello outside the Coop. Their favourite was “Autumn Leaves.” Whenever I packed up they would ask me when I was coming back, as if I was a real musician. And they were generous, too. I busked twice a day, once in the morning and once in the afternoon, and it became a happy ritual to empty the pockets of my torn and faded jeans out onto the plywood offcut that served as my kitchen, and count my coins. One day I counted eight hundred kroner. Eighty pounds. It seemed nothing short of miraculous.

I could have stayed longer in Mo i Rana, but time was running out. It was already too late to see the midnight sun in Bodø, a few hundred kilometers further north. If I was lucky I might just make it to Tromsø. I left on a Sunday and traveled west to the Kystriksveien, a coastal route that passes close to the Svartisen glacier. Andrew had always wanted to see a glacier.

Part of the Kystriksveien is a sea ferry. I left my van in a queue of three, in a tiny harbor called Kilboghamn, and went to stand on the edge of a stone pier. The sea was slapping up against enormous tractor tires fifteen feet wide, indicators of how intense the winter storms must get up there. An icy wind was blowing. I went back to the van and changed my flip-flops for boots and socks and made a flask of tea. By the time I finished the ferry had arrived.

Up on deck I was alone. The other travelers sensibly sat inside, out of the wind, behind the salt-caked windows. I breathed wet, salty air and listened to the restless crying of gulls. Above me clouds raced across the sun. Rocks eroded by ice towered over the water, casting strange shadows. A handful of courageous trees clung to threadbare slopes. From here the land looked bald, as if it had been scoured with a Brillo pad. The wind caught the sea and whipped it into frothy waves.

A couple of fishing huts with their windows boarded up clung to the shoreline.

We passed a lone green buoy. There was a loud blast and a voice crackled into life over the loudspeaker.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” it said, in Norwegian and then in English.

“Welcome to the Arctic Circle.”

12

I busked in Bodø and then traveled east to Narvik, an industrial port that’s only a city by Norwegian standards. The scene of bitter wrangling during World War II, it’s not an aesthetically pleasing place. After three days sitting outside the shopping center trying to avoid eye contact with security, I was relieved to be back on the E6. Doubly so this time, because my next stop, in just 180 miles, was Tromsø. I imagined tree-lined streets and old stone buildings, pavement cafés and jazz musicians. I was nearing my goal. The long journey would soon be over.

I drove faster than usual that day, and the one after, reaching Tromsø on the evening of 22 July. Not a day too early. Crammed on to an island called Tromsøya, one of hundreds of islands and islets in an archipelago surrounded by deep and very Arctic-looking fjords, Tromsø is on the far side of a long and elegant bridge. Beside the bridge was one of the weirdest buildings I had ever seen—a kind of huge, white, triangular caterpillar. I later learned that it was a church, nicknamed the Arctic Cathedral. I found it extraordinarily beautiful. Behind the church was Tromsø’s tallest mountain, the Tromsdalstinden, which had a dusting of snow even on 22 July. The church, the mountain, and the snow seemed to live up to my grand expectations. I was jubilant. I had made it in time to see the midnight sun. I was also closer to the North Pole than I was to my shed in the garden of Broadsands.

I crossed the bridge and drove up the main street, which was deserted. There were no old stone buildings. There was an old-looking pub, called the Ølhallen, with some old-looking men outside. But it was made of wood. There was a very prosaic Narvesen newsagent, with covered steps outside, that looked like a promising pitch. There was something called the Polaria, which seemed to be some kind of cross between a museum and an aquarium, with polar bears on the sign. There were some grocery stores: a Coop and a Rimi. A little bit further along there was a phone box. And that was it. I drove along the fjord and then spent an hour lost in the suburbs, looking for a place to park up for the night and watch the midnight sun. But there were too many houses crammed on to the tiny island, and the only places you could park seemed to be graveyards.

I stuck to the road nearest the water, which took me through a tunnel and along the north edge of the island. It was getting late. The jagged mountains on the other side of the water looked wild and untameable. They belonged to the Arctic of my imagination. There was a sharp wind blowing from the north, and although it wasn’t cold, the wind on the fjord made it look cold. It felt like a place where humans were merely squatting, as if at any moment the whole city could be reclaimed by the wilderness that encircled it, the houses crushed by the weight of the mountains, the streets turned back into frozen fjords. Nothing could have been less like Paris.

Eventually I found a place to park. It was called Sydspissen, and it was at the end of a short dirt track on the corner of the island where south becomes west. There were no houses, apart from a crumbling yellow building that was covered in graffiti. There was a beach of sorts—at least, there were boulders that led to the edge of the cold-looking fjord. There were no vehicles, just a lone wooden canoe pulled up on its side, as if it had been abandoned.

I don’t know what I was expecting. A welcoming committee, perhaps. Somebody to pat me on the back and say well done. Some Parisian-style bar, where I could treat myself to a glass of red wine and tell everyone about my great achievement. And what about the midnight sun? That thing I had come so far to see. Jan Erik’s friend had definitely said you could see it from Tromsø, but I had driven all over the island and I hadn’t found anywhere with a clear view of the sky. There were too many of those jagged mountains getting in the way.

I parked the van so the back doors were facing the mountains. I made a cup of tea and took it t

o the beach. I sat on one of the boulders with a blanket wrapped around my shoulders. And I waited for midnight. And midnight came and went, and it didn’t get dark, but the sun was not bouncing around on the horizon, or if it was, I couldn’t see it.

The next morning I left the van where it was and walked back to the main street along the Strandvegen, carrying my cello. It was a long walk, and by the time I reached the steps outside the newsagent my back was aching and I had a painful blister on my right toe where my flip-flop was rubbing. I unpacked my cello and tried to feel good. I had done it. I had busked my way to the midnight sun. It wasn’t the way I had expected, but that was life. Things had never been the way I expected. Obviously the midnight sun was symbolic. It didn’t really exist. It was a way of saying that it never got dark, and it hadn’t got dark. I had forgotten what dark even looked like. I tried to count my blessings. There were no panpipes, the pitch was good, and once I had made enough money I could turn around and go home, and nobody would be able to say I told you so.

On my way back along the Strandvegen I stopped to buy an international phone card. I swam in the fjord, which was full of rocks and seaweed, but better than nothing, and changed out of my shorts and into my torn and faded jeans. They were covered in tiny pieces of seaweed from being washed in fjords. I walked back along the fjord until I reached the phone box near the Rimi. The blister was hurting so much I had to take my flip-flops off and walk barefoot.

Ben answered the phone.

“I’ve done it. I’m at the midnight sun.”

“Fuck. You’re never at Nordkapp?”

“No, Tromsø. But you can still see it here. Or you could last night.” In theory anyway. “Tromsø is the Paris of the north, you know.”

“Fuck.”

“More like Penzance.” I tried to laugh but actually I wanted to cry. I gripped the receiver. “Anyway, I’m coming home now. I can’t wait. I can’t wait to sit in the bar with you and drink Rattler and not have to worry about the van breaking down and how much diesel I’ll need to get to the next town. The distances are massive. You’ve got no idea. There’s one sign when you leave Trondheim. One road sign. And all it says is Narvik, nine hundred kilometers …”

I noticed that Ben was unusually quiet. My heart was crashing violently against my rib cage. I knew something was wrong.

“Are you okay?”

There was a horrible pause.

“Jack’s back.”

I let myself slide down the glass until I was sitting on the cold concrete floor. Thank God. Thank God. Thank God.

“Can I speak to him?” I mumbled incoherently.

Silence.

“Ben?”

“Christ, I shouldn’t be the one …” said Ben.

“The one what?”

“He’s got a fucking girl with him.”

There were ants on the floor. Little red ones, bustling around like office workers.

“Are you still there?”

“A girl?” I said, eventually, in a voice I hardly recognized. “What kind of girl?”

“Sweet, I suppose. Petite.”

I held the receiver at arm’s length like it was a bomb about to detonate. But I could still hear him.

“Surfs,” he was saying. “Wears technical trousers. Are you okay?”

I could hardly breathe.

“Where are they living?” I croaked.

But I already knew the answer.

“Um, in the shed. For now. Just until they find somewhere better.”

“My shed?”

“Fuck. I mean, it’s his shed really. He’s the one …”

I dropped the phone. I leaned against the glass. I couldn’t even cry.

Part Two:

The Midnight Sun

13

Not crying didn’t last long. It was as if someone had screwed a corkscrew into my chest and was slowly pulling out my heart with it. I cried all the way back to the van. I cried all night. I cried all the way back to the newsagent the next day. I cried while I busked, tears squeezing themselves out from under my closed eyes. I didn’t care anymore. And I didn’t play “Summertime,”either. I stopped trying to be cheerful and dredged up the most tragic-sounding thing I knew; Rachmaninoff’s “Vocalise.” It’s a beautiful piece of music and I love it with all my heart, but even I knew it was utterly unsuitable for a sunny summer’s day in the Arctic. I played it anyway, over and over again, and to my great surprise people took to standing around in groups to listen. Sometimes they even applauded. They all gave me money. I was making more money from playing Rachmaninoff’s “Vocalise” than I’d ever made in my whole life. At this rate I could be home in a couple of weeks.

Only there was no home anymore.

I cried in the Rimi supermarket where I bought cheap bottles of beer to drink on the bouldery beach, in the hope that it would knock me out. It never did. Instead I lay in bed for hours every night, watching a film on the inside of my eyelids of Jack and some sweet petite surfer in technical trousers having sex in our bed, and woke up with a crashing headache. I longed for darkness. But instead of darkness there was the bloody midnight sun shining on and on and on, like a bad joke.

I was still crying four days later when Henrik crossed the street and dropped a pair of yellow sunglasses in my hat. He was tall, and had laughing brown eyes and a suit with the shirt open at the collar. He waited until I stopped playing. I picked up the sunglasses.

“Try them,” he said.

I put the sunglasses on and the street was transformed with what I can only describe as a kind of late afternoon, Californian haze. Not that I’d ever been to California.

“Thanks,” I mumbled.

“No problem.”

He carried on standing there, blocking me from the street.

“Um, do you mind moving?”

He didn’t move. Instead, he said, “How would you like to make five hundred kroner in twenty minutes?”

Oh God.

“I think you play nice.”

“Look …”

“And you look nice, too.”

What was it about playing a cello? Did the curves remind all men of naked women, or was it the way you had to sit with your legs open to play it?

“Thanks.”

Henrik smiled.

“But I’m not a prostitute.”

Henrik held up a hand and shook his head.

“No, that is not what I mean. There is a bachelor party in the Ølhallen for my friend.”

“Bachelor party?”

He clicked his fingers a few times.

“He is getting married.”

“Stag night.”

“Ja! Stag party. It will be very funny if you play your cello.”

It sounded pretty funny. It sounded like the most horrible, laughable, embarrassing thing I’d ever heard of.

“Why not?” I said.

I didn’t much care what happened anymore.

The Ølhallen is the oldest pub in the Arctic Circle. It’s attached to the Mack brewery, which is where they make the Arctic beer I had drunk with Aase Gjerdrum all those weeks ago. There was a deathly hush when I entered. This was probably because the Ølhallen was empty, save for a couple of old men propping up the old wooden bar and a giant cardboard polar bear. It was also, I suspected, because I was the first female to walk through the door since 1794 when Tromsø received its municipal charter.

It wasn’t empty for long. I barely had time to install myself in a dark corner before fifteen drunk and noisy Norsemen came crashing in and squashed themselves onto two tables right next to me. Luckily, within about five minutes nearly every single one of them had bought me a bottle of Arctic beer.

I downed one of the bottles and lined the others up on the floor. I tried to breathe. This was not busking. This was not a busy street full of people who might or might not hear a snatch of something and like it enough to throw me a coin. This was a pub full of men who had already paid me to play and were silently waiting for me to begin.

In short, this was all of my worst nightmares rolled into one. This was a gig. I downed a second bottle of Arctic beer and closed my eyes.

“That was very nice,” said Henrik an hour later, after I had put my cello away and squeezed myself onto the bench next to him.

“Really?”

I felt almost high on adrenaline. Or maybe it was relief. Or maybe it was Arctic beer.

“Yes, but you play for too long. You play for an hour. I say twenty minutes.”

“Shit. Sorry.”

“Now I must pay you more.”

He put two more five-hundred-kroner notes down on the table.

“You’ve already given me five hundred!”

“Five hundred for twenty minutes. That was our deal.”

He picked up the notes and tucked them into the pocket of my jeans himself. The equivalent of a hundred and fifty pounds. I tried not to notice his hand sliding over my stomach. The man on the other side of me introduced himself as Yoghurt.

“Summertime and the living is heasy,” he warbled. “In winter we have underfloor heating in the streets, because otherwise we would die of cold.”

“Crikey.”

Yoghurt’s ancestors were Sami nomads.

“You like the sunglasses?” said Henrik.

I’d forgotten all about the sunglasses. No wonder it was so dark in there. I pushed them on to my head. Everything looked crap again. I reached for my latest bottle of Arctic beer.

There are two types of people in this world. The type that is made for serious beer drinking and the type that isn’t. I belong to the latter category. Six bottles was easily my personal best.

I reached for my seventh. After my seventh bottle I decided that Henrik was quite good-looking. Even though his shoulders were too narrow. His hand was stroking my knee.

“What are you doing in Tromsø?”

The Ribbons Are for Fearlessness

The Ribbons Are for Fearlessness